|

| Image: C2PA |

It's been a few years since Adobe started testing Content Credentials in Creative Cloud apps, and a year since the company announced it'd use them to mark images generated by its Firefly AI. If you're unfamiliar, Content Credentials aren't just about AI; they're also pitched as a secure way to track how images were created and edited in the hopes of slowing down the spread of misinformation. Adobe bills the system as a "nutrition label" for digital content.

At Adobe's MAX conference, we got to sit down with Andy Parsons, Senior Director of the Content Authenticity Initiative at Adobe, and ask him some questions about Content Credentials. Given the opportunity, it also seemed like a good time to check in with the system.

Content Credentials on the Web

Earlier this year, Adobe began rolling out support for adding Content Credentials to your photos in Adobe Camera Raw, Lightroom, and Photoshop. These features are still currently in Early Access or Beta. There's also a Content Credentials verification site that anyone can use to inspect image, video and audio files to see if they have Content Credentials attached or if they've been watermarked with a link to Content Credentials.

However, the company is also looking to make the tech available even to people who don't use its products. This month, it announced a private beta for a Content Authenticity web app. The site lets people who have joined via waitlist upload a JPEG or PNG and attach their name and social media accounts to it after verifying ownership of those accounts by logging in to them. After the person attests that they own the image or have permission to apply credentials to it – there's currently no way to verify that's actually true – it lets them download the image with Content Credentials attached. The tool also lets you attach a piece of metadata, asking companies not to use your image for training AI.

Adobe doesn't aspire to store every content credential in the universe"From the beginning, before we wrote the first line of code for this tool, we asked creators in the Adobe ecosystem and outside the Adobe ecosystem what they wanted to see in it," said Parsons. "We got a lot of feedback, but we haven't finished this. So the private beta is meant to last a few months, during which we'll collect more feedback."

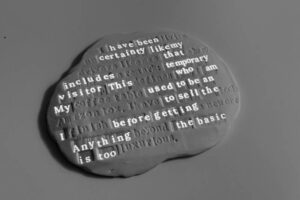

The system also adds an invisible watermark to the image that links to the credentials stored on Adobe's servers. If someone tries to strip that information out of the image or takes a screenshot of it, it should be recoverable. If someone alters the image, the credentials will theoretically disappear, and the image will no longer be verified as authentic.

"Photoshop users don't want a watermark that somehow changes the look or adds noise to an image that has it. So we did a lot of work to make sure that this was noise-free, that it works with images of very different resolutions and different kinds of color content," Parsons said.

The site is an example of how Content Credentials can work, but if the technology becomes widespread, there'll likely be many more like it. "Adobe doesn't aspire to store every content credential in the universe," Parsons said. "That's why an interoperable standard is so critical. Getty Images could host its own content credential store. Adobe has ours. Someone else could do this on the blockchain; it's really up to the specific platform."

Storing content credentials doesn't require as much storage as it may seem. "We don't store your image; we're not building a massive registry of everyone's content. We store just that 1KB or so of cryptographically signed metadata. And anyone can do that."

|

|

Attached Content Credentials are one of the signals Meta looks for when generating its 'AI Info' labels on Facebook, Instagram, and Threads. Image: Meta |

Some websites have also started using Content Credentials to provide additional context for images and videos. According to Parsons, Meta uses Content Credentials as a signal when applying the "AI Info" label it uses for Instagram, Facebook, and Threads.

YouTube has also begun using Content Credentials to label videos posted on its site. If someone uses a camera or app that attaches credentials to a video and doesn't make any edits to it, the video will receive a "Captured with a camera" label meant to certify that what you're seeing is an unaltered version of what the camera captured.

Adobe also recently released the Adobe Content Authenticity extension for the Chrome browser, which surfaces Content Credentials on any site if it detects images that have them attached. "I think of it as sort of a decoder ring," said Parsons. "Once you install the decoder ring, you can see all the invisible stuff on the web."

|

| The Chrome extension can pick out images with Content Credentials, even if the site they're hosted on doesn't natively tag them. |

He anticipates that, someday, the extension won't be necessary and that the information it provides will be more broadly available. "Of course, it really belongs in web browsers and operating systems," he said. "I do anticipate a fair amount of work in the next 12 months going into browser support from folks like Microsoft and Google and others. That's really the big next step."

A not-so-seamless experience

We ran into some strange behavior when testing these tools, though the issues were limited to how they were being displayed – or rather, not displayed – on the web. We added an AI-generated element to two images using Photoshop, then exported and uploaded them to Instagram.

The Content Credentials inspection site properly identified the images as having been edited and showed the changes we'd made. Instagram, however, only added the "AI Info" option to one of them and not the other, despite them having gone through the same chain. The label never showed up when the same images were posted to Threads. When we opened the images on Instagram, Adobe's Chrome extension said there were no images on the page with Credentials attached, though it's worth noting that the tool is still in beta.

Adobe's verification site successfully recovered the credentials after we hit the "Search for Possible Matches" button. However, there's clearly still a long way to go before sites can reliably use Content Credentials to provide information about an image's providence or to identify images that were made or altered using AI image generation. That's certainly a bit disappointing, as photographers and artists hoping to use the system to watermark images uploaded to social media as their own can't necessarily rely on it yet.

It's also worth noting that our test was essentially the best-case scenario; we made no efforts to hide that AI was used or to remove the Content Credentials. But while it does show cracks in the ecosystem, Content Credentials not showing up on an image that should have them is a much better outcome than if they had showed up on an image that shouldn't.

New Cameras with Content Credentials

During Adobe Max, Nikon announced that it's bringing Content Credentials to the Z6III at some point next year. During a demo at Adobe Max, images taken with the Z6III had credentials attached verifying the time and date they were taken and information about the ISO, shutter speed, and aperture used.

Currently, it seems like the function will be limited to professional users, such as photojournalists.

What's left to do?

Despite the ecosystem improvements, there's absolutely still work to be done on Content Credentials. When we tested the system in July, we found a surprising lack of interoperability between Lightroom / ACR and Photoshop, and the issue still persists today. If you make edits to an image in Lightroom or ACR, then open it in Photoshop and save the file with Content Credentials, there won't be any information about what you did in ACR or Lightroom. You can work around this by saving the file from Lightroom or ACR as a PNG or JPEG and then opening that in Photoshop, but obviously, that's not an ideal workflow.

That watermarking durability guarantee is importantThe tools for incorporating Content Credentials into video are even less mature. Parsons says there are some third-party tools starting to support the metadata, such as streaming video players, and that Adobe is working on applying the invisible watermarks to videos as well. "For us, that watermarking durability guarantee is important. And we'll have video with that – I can't put a date on it, but that's something that we're very focused on. Same for audio."

Then there's the issue of cameras. Even if you have a camera that theoretically supports Content Credentials, such as several of Sony's flagships or the Nikon Z6III, you almost certainly can't use them. Both companies currently treat it as a feature exclusively for businesses, governments and journalists, requiring special firmware and licenses to enable it.

To be fair, those entities are generally the ones producing images where Content Credentials will be the most important. Most photographers' work doesn't require the same level of transparency and scrutiny as images released by law enforcement agencies or photojournalism wire services. However, in an age where news is increasingly documented by regular people using their cell phones, the feature will have to become available to average consumers at some point to have any hope of gaining traction.

I don't think anybody cares how secure a picture of my cat is.One camera manufacturer is letting people use Content Credentials out of the box: Leica. Its implementation also uses special hardware, similar to Apple's Secure Enclave or Google's Titan chips, which are used to store biometrics and other sensitive data, instead of relying on software. Nikon's Z6III also features hardware support for Content Credentials, unlike the Z8 and Z9. In reference to the information stored on Apple's chip, Parsons said, "Three-letter agencies in the U.S. government don't have access to that, neither does Apple in this case. So that's the vision that we have for cameras." According to him, "If you want ultimate security and a testament to the fact that the camera made a particular image, we'd prefer to see that as a hardware implementation."

He did, however, re-iterate that there are times when that level of security isn't necessary. "If you are the NSA or a government or somebody working in a sensitive area... Maybe somewhere where your identity could be compromised, or you'd be put in harm's way as a photojournalist, you probably do want that level of security. And certain devices need to provide it. Think about a body-cam image versus my picture of my cat. In the former case, it's probably very important because that's likely to see the scrutiny of a court of law, but I don't think anybody cares how secure a picture of my cat is."

Content Credentials and other authenticity systems are only part of building trust in an age of generative AI and widespread misinformation campaigns. "This is not a silver bullet," Parsons said. "It's not solving the totality of the problem. We know from many studies that many organizations have done in many parts of the world that people tend to share what fits their worldview on social media. In many cases, even if they know it's fake. If it fits your point of view and you want to further your point of view, it almost doesn't matter."

"This is not a silver bullet"Instead, Parsons views Content Credentials as one of the tools people can use when deciding to trust certain sources or pieces of content. "If somebody receives an image that someone has deliberately shared, you know, misinformation or deliberate disinformation, and can tap on that nutrition label and find out for themselves what it is, we think that fulfills a basic right that we all have."

3 weeks ago

25

3 weeks ago

25

English (US) ·

English (US) ·