![]()

For several decades, there were two big names — both of which happened to be German — in the 35mm camera world that stood like skyscrapers among all companies. You’ve undoubtedly heard of both of them: Carl Zeiss and Leitz Camera, more commonly known as Zeiss and Leica.

It may not surprise you that these two companies weren’t exactly pals, and the rivalry between Zeiss and Leica in the 1930s and 1940s is one of the most intense competitions between two pioneering giants in photographic history. Both brands were heralded for their innovative engineering and design and significantly shaped the landscape of 35mm photography, but this period was not just about technological innovation; it was also about the profound impacts on photojournalism, art, and consumer culture.

The History of Zeiss

The history of Zeiss, one of the most esteemed names in optics and optoelectronics, begins in 1846 in Jena, Germany, when Carl Zeiss, a skilled mechanic and precision engineer, founded a small workshop. Initially focused on repairing and manufacturing scientific instruments, Zeiss quickly recognized the potential for innovation in optical devices. His early work centered on microscopes, and by 1847, Zeiss was producing simple microscopes that were well-regarded for their quality.

![]()

A significant turning point in the company’s history came in 1866 with the partnership between Carl Zeiss and physicist Ernst Abbe. Abbe brought a rigorous scientific approach to the development of optical instruments, which was crucial for advancing the precision and performance of Zeiss’s products. Abbe’s contributions included the Abbe sine condition and the formulation of what would become known as the Abbe number — both critical in the design of advanced optical systems. Under Abbe’s influence, Zeiss microscopes became renowned for their superior resolving power and clarity, establishing the company as a leader in the field.

In the 1880s, another pivotal figure, Otto Schott, joined forces with Zeiss and Abbe. Schott, a chemist specializing in glass, developed new types of optical glass that allowed for the creation of lenses with unprecedented clarity and minimal distortion. However, in the late 19th century, Zeiss expanded its scope to camera optics under the guidance of physicist Ernst Abbe and optician Paul Rudolph.

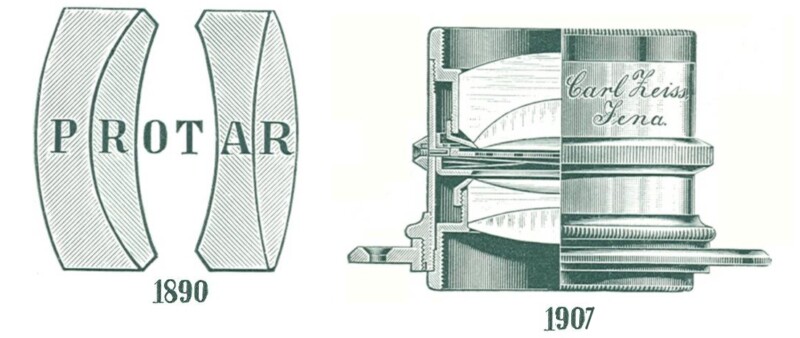

CC-BY-SA 3.0

CC-BY-SA 3.0The anastigmat (or anastigmatic) lens was engineered to correct the three primary optical aberrations: coma, spherical aberration, and astigmatism. Its asymmetric design was comprised of four elements, with two achromatic lens doublet groups. The front divergent group corrected for spherical aberration, while the convergent rear group reduced field curvature and corrected astigmatism. The landmark design by 32-year-old Paul Rudolph — with glass from Otto Schott — successfully imbued an asymmetric design with the benefits of a symmetrical lens (low chromatic aberration, distortion, and coma). In 1890, Zeiss filed a patent for the design, calling it the Protar.

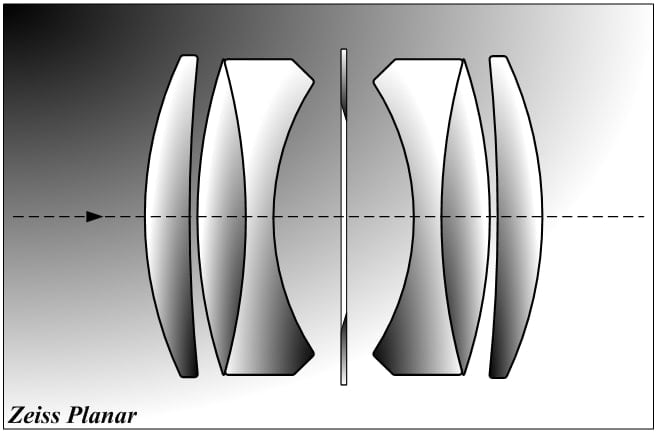

The original 1896 Zeiss Planar design | CC-BY-SA 3.0

The original 1896 Zeiss Planar design | CC-BY-SA 3.0By the early 1900s, Zeiss had become a global leader in optical technology. Under the expertise of Rudolph, the company developed the revolutionary Planar design in 1895, the Unar in 1899, and the Tessar in 1902. The company’s commitment to innovation was further exemplified by the creation of the first modern planetarium projector in the 1920s, which revolutionized the way astronomical education was conducted. Zeiss also played a significant role in the development of cinema projection lenses and contributed to advancements in military optics during World War I, producing rangefinders and periscopes.

The interwar period saw further expansion and diversification. In 1926, Zeiss merged with several other optical companies to form the Carl-Zeiss-Stiftung, a foundation aimed at ensuring the continuity and independence of the company. And, in 1932, Zeiss entered the camera game in a bid to compete against its Wetzlar counterpart. But more on that in a minute.

The History of Leica

Like Zeiss, the history of Leica began in the mid-19th century with the establishment of Ernst Leitz Optische Werke, a German company based in Wetzlar founded by Ernst Leitz in 1869. The company initially specialized in manufacturing high-quality microscopes and optical instruments — it was not until the 1920s that Leica would revolutionize photography and become a household name.

The Ur-Leica | Photo by Leica

The Ur-Leica | Photo by LeicaThe genesis of Leica cameras can be traced to Oskar Barnack, a visionary engineer working for Leitz. Barnack’s primary interest lay in creating a small, portable camera that could use standard 35mm cinema film — a stark contrast to the bulky large format plate and negative cameras of the era. So, in 1913, Barnack developed the Ur-Leica, a prototype that featured a compact design and a revolutionary approach to film advancement. By running the film horizontally instead of vertically as cinema cameras did, the smaller-format 35mm film could be used to produce a 24x36mm negative — twice the size of an 18x24mm cinema frame. It was fitted with a 50mm f/3.5 lens, newly designed by Professor Max Berek to suitably cover the larger frame size, named the Leitz Anastigmat.

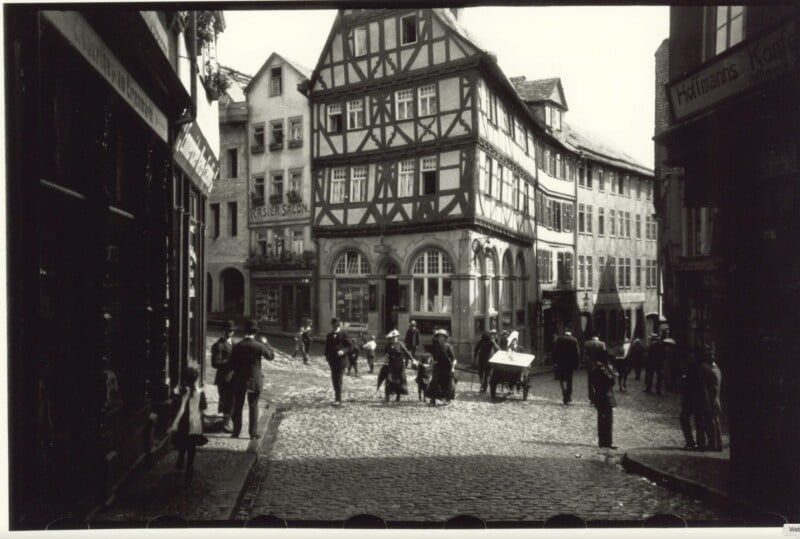

First photo taken on a Leica | Photo by Oskar Barnack

First photo taken on a Leica | Photo by Oskar BarnackWorld War I delayed further development, but by the early 1920s, Barnack’s concept was revived. In 1923, Ernst Leitz II, recognizing the potential of Barnack’s invention, was convinced to proceed with pre-production of 31 cameras. The first commercial Leica camera, the Leica I (sometimes referred to as the Model A), was introduced two years later, in 1925, at the Leipzig Spring Fair. It was an immediate success, praised for its portability, ease of use, and exceptional image quality — the latter primarily due to Berek’s redesigned four-element/three-group lens, now named Elmar. While the first commercially sold 24x36mm stills camera was actually the American-made Simplex Model B in 1914, the Leica I is the camera that cemented 35mm as a viable and popular stills medium, igniting a spark that would fundamentally change the industry forever.

Leica’s commitment to quality and innovation extended beyond camera bodies to lenses as well. The company developed a range of high-quality interchangeable lenses throughout the 1930s, such as the Summar, Hektor, Summitar, and Xenon, which became renowned for their optical performance. One could easily make the case that the lenses, as much as the cameras, contributed to Leica’s eventual reputation as a producer of some of the best photographic equipment in the world.

Enter: Contax

The rivalry’s roots can be traced back to the early 20th century. After Leica — a relative upstart of a company compared to Zeiss — launched the first practical 35mm camera in 1925, it was inevitable that other companies would soon follow suit with their own attempts. Zeiss Ikon of Dresden chose Dr. Ing. Heinz Küppenbender as the chief designer to answer the call. Zeiss, arguably the world’s most innovative and influential optical company of all time, was determined to produce a superior camera.

The Leica I | CC-BY-SA 2.0

The Leica I | CC-BY-SA 2.0Before we continue, let’s quickly go over the design of Leica’s trailblazing camera for those who are unaware.

The Leica I was a very small, compact, and lightweight camera fitted with a non-interchangeable, uncoated 50/3.5 Elmar — based on the venerable Cooke triplet design — that could neatly collapse into the body for more compact storage. When ready to use, the lens was pulled out and rotated to lock it into position. The Leica I had no built-in rangefinder, so scale-focusing was, in most cases, the only option, requiring the user to estimate the focus distance and set it on the lens accordingly.

Why did I say “in most cases”? Because Leica did offer a (rather absurd looking) vertical rangefinder accessory that slid into the camera’s cold shoe and gave photographers the ability to look through the rangefinder, align the images by rotating a small wheel, read the distance that was measured, and finally transfer that distance to the lens’s focus scale. Needless to say, it was both physically and logistically cumbersome, especially if you were also trying to frame through the camera’s viewfinder.

Leica II fitted with a 135mm lens and external viewfinder | CC-BY-SA 2.0

Leica II fitted with a 135mm lens and external viewfinder | CC-BY-SA 2.0The battle between Zeiss and Leica was predominantly fought through technological superiority. Leica’s cameras were renowned for their simplicity, compact design, and the exceptional quality of their lenses. The Leica II, introduced in 1932, became a new landmark model by incorporating a built-in rangefinder and viewfinder — a massive improvement over the scale-focusing of the Leica I — and interchangeable lenses.

Contax I | CC-BY-SA 2.0

Contax I | CC-BY-SA 2.0Zeiss’s response to Leica’s innovations — the Contax I — also featured an integrated rangefinder but boasted a more advanced, vertically traveling shutter made from metal blades. This allowed for higher shutter speeds up to 1/1000 of a second. This was an area where the Contax held a technical edge over Leica, whose cloth shutter curtains initially limited their speeds.

Contax IIA ad

Contax IIA adIn subsequent models, both companies continued to innovate. Zeiss introduced the Contax II in 1936, which refined the rangefinder mechanism and improved overall reliability. This model was quickly followed by the Contax III in 1938, featuring a built-in exposure meter, one of the first cameras to offer this technology.

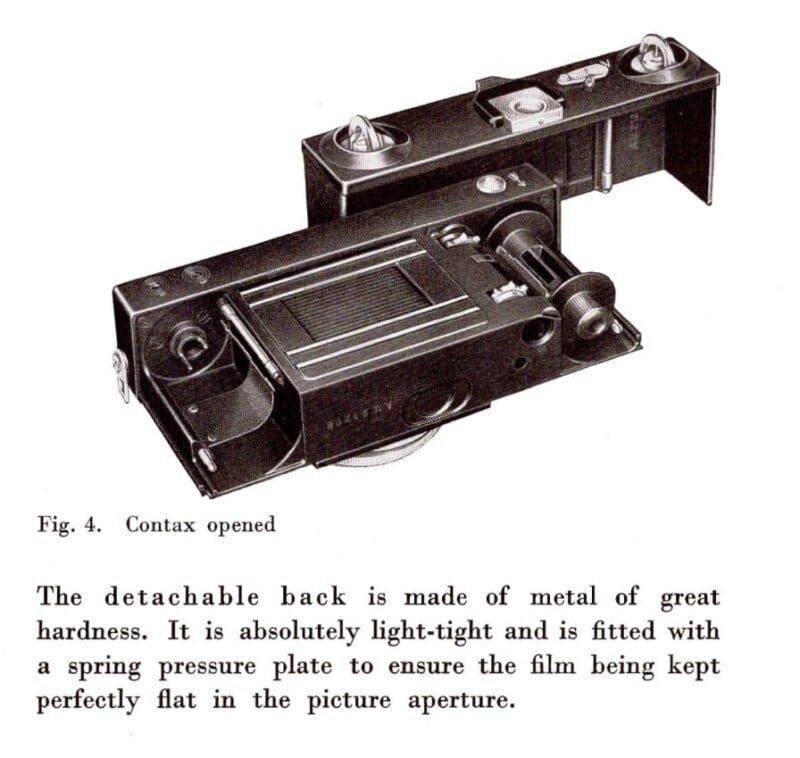

The detachable back of the Contax made film loading significantly easier than the Leica

The detachable back of the Contax made film loading significantly easier than the LeicaLeica continued to refine its designs with the Leica III, which offered a range of shutter speeds and improved the rangefinder and viewfinder. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, Leica and Zeiss not only competed on features but also on the optical quality of their lenses, with each brand supported by outstanding optical engineers. Carl Zeiss lenses for Contax and Leitz lenses for Leica were both highly regarded, offering superior sharpness, contrast, and character.

World War II and Its Impact

The onset of World War II had profound implications for both Zeiss and Leica, affecting not only their operations but also how their cameras were used in the field. During the war, cameras became vital tools for war correspondents and were often requisitioned for military use. Leica and Contax cameras were highly sought after by both Axis and Allied photographers.

Leica’s reputation was somewhat shielded by its apolitical stance and the universal respect for its engineering excellence. The company faced significant challenges, including the difficulty of maintaining production due to material shortages and the complexities of operating in Nazi Germany. However, Leica also engaged in covert activities, such as helping Jewish workers escape the Nazis by assigning them abroad.

Zeiss, being in Dresden, found itself in a more precarious position. The city was heavily bombed during the war, severely impacting Zeiss Ikon’s production capabilities. The factory was eventually captured by Soviet forces in 1945, and much of its technology and machinery were relocated to the Soviet Union, influencing post-war Soviet camera design and production.

Influence on the Photographic Community

The ease of use of both Contax and Leica cameras, coupled with excellent optics, allowed photographers to explore new techniques such as candid photography, street photography, and the comprehensive documentation of events as they unfolded, which was particularly crucial during the war years.

FRANCE. Normandy. Omaha Beach. The first wave of American troops lands at dawn. June 6th, 1944.

FRANCE. Normandy. Omaha Beach. The first wave of American troops lands at dawn. June 6th, 1944.Photographers like Robert Capa made extensive use of Contax cameras during the war due to their higher shutter speeds, which were ideal for capturing fast-moving action on the battlefield. Meanwhile, Leica’s cameras were favored by Henri Cartier-Bresson, who appreciated the compactness and the quiet operation of the Leica, ideal for his pioneering candid and street photography.

Robert Capa with his Contax II

Robert Capa with his Contax IIWhile Capa originally started with a Leica III, he soon moved to the Contax II, which was used to capture some of the most famous D-Day images at Normandy Beach, as well as the portrait of a Chinese child soldier that graced the cover of Life magazine. Cartier-Bresson, on the other hand, was a lifelong Leica user.

Robert Capa’s famous Life magazine portrait, taken with a Contax II

Robert Capa’s famous Life magazine portrait, taken with a Contax IIThese photographers not only pushed the technological capabilities of the cameras but also established a visual style that would define photojournalism and documentary photography for generations. Their work during the war and in the years that followed contributed to some of the most enduring images of the 20th century, cementing the status of both brands in the annals of photography history.

Henri Cartier-Bresson’s first Leica | CC-BY-SA 3.0

Henri Cartier-Bresson’s first Leica | CC-BY-SA 3.0After World War II, the photography industry saw significant changes. Leica managed to quickly regain its footing, continuing to innovate with new models and eventually transitioning into the digital age. The brand maintained its reputation for precision and quality, adapting its traditional designs to new technologies and market demands.

One of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s most famous photos

One of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s most famous photosZeiss, however, faced a more turbulent path. The original Dresden facilities suffered from the aftermath of the war and subsequent Soviet occupation. Although Zeiss attempted to re-establish the brand in West Germany, producing cameras under the Contax name until 2005, it never regained its pre-war prominence. The company even produced the first full-frame digital camera, but it found little success against Japanese juggernauts Canon and Nikon.

Two Legendary Brands

One of Contax’s last cameras, the Contax N Digital | Photo by KEH

One of Contax’s last cameras, the Contax N Digital | Photo by KEHThe rivalry between Zeiss and Leica was more than just a competition between two camera manufacturers; it was a crucible in which modern photography was forged. Through their innovations and the legendary photographers who used their cameras, Zeiss and Leica contributed to the evolution of visual culture. Their impact extended beyond the technical aspects of photography, influencing the aesthetics of visual storytelling and the way we perceive the world through images.

Leica’s newest camera, the Leica M11, in glossy black paint

Leica’s newest camera, the Leica M11, in glossy black paintThe rivalry between Zeiss and Leica during the 1930s and 1940s is a landmark chapter in the history of photography. It was characterized not only by fierce competition but also by profound innovations that shaped the future of photographic technology and aesthetics. The legacy of their rivalry is still evident today, as modern digital cameras continue to evolve from the mechanical and optical foundations laid by these two pioneering brands. Through their competition, they pushed each other to achieve greater heights — and we’re all better off because of it.

Image credits: Elements of header photo licensed via Depositphotos.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·